|

This is a quick ten-minute podcast on how to search for sources for my Natural Science Biology Laboratory. This tells you how to use Google Scholar, how to cite your sources, and how to format the sources using Google Docs.

1 Comment

Teachers today have a lot to compete with, when it comes to students and their cell phones. If I were a little bird in the back of the lecture hall during my talks, I can only imagine how many students are using their phones, iPads, or laptops to view funny videos from Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube. Maybe the students are present, but they sure aren't engaged. The new war in the classroom is teacher versus technology. Is zero tolerance for cell phones in the classroom realistic, or even smart? Really, the only way to beat them is to join them - and by join them, I mean give them something smart to do with that phone.

I use Youtube videos extensively in my biology lab for a multitude of different ways to supplement learning. Up until this semester, I have always projected the videos onto the big screen. When I talk about the dangers of DDT, I show videos of soldiers spraying DDT onto prisoners from Japanese internment camps to kill lice, of bald eagles sitting on their nests full of broken eggs, and how the pesticide bioaccumulates in living tissue. Just telling students about these topics is one thing - but showing them historical evidence, the way it happened in nature, and the way the chemicals interact brings the science to life. 1. Making microscopic interaction visible: “Back in the day when I learned chemistry, there was no YouTube, no videos, and you just had to imagine molecules moving and hitting each other,” Chemistry teacher Jasen Gohn said. “But now you can just bring up a video of, like, salt dissolving.” For my Biology students, reactions like diffusion or osmosis can be made large enough to see. I can also equate the processes to real bodily functions, like kidney dialysis, which brings the human elements to what might have been considered "boring" in the past. Showing my students pictures of DNA and Watson and Crick are one thing - showing them the actual structure of DNA and the way it functions to make life possible is much better. In Biology, much of what happens at the cellular, molecular, and chemical level is not visible to the naked eye. Videos make these interactions viewable. 2. Watching a lecture for one hour is often boring Many college classes last between 50 and 90 minutes. One study noted that students can pay attention for between 10 and 15 minutes before they look away, stop taking notes, or look at their electronic device. Towards the end of class, note taking ceased, and students could only pay attention for 3 - 4 minutes. Youtube videos can be an engaging, good "distraction" from the traditional lecture. Videos can break up the monotony. 3. More demonstrations can happen in the classroom Demonstrations are often used for convenience, when the entire class doing an activity would be prohibited by cost or time. When using video demonstrations, students can watch the teacher, instructor, scientist, or star doing the demo on video. Not only is this more economical, it's often more fun. If a student was not paying attention during class (as often happens in this new age of students who work full time, are parents, or who may be distracted) they still have the opportunity to to view the video later. 4. Whether there are 20 or 200 students in the room, each student can have a front row seat. Anyone who has taught a lab-based science course knows that you often have to go around the room, from lab bench to lab bench, repeating the technique so the students can be close enough to see. In a large lecture, an Elmo-device (basically a stereoscope that projects the demo to a big screen) might make the demo big enough, but it is often difficult to see. When I teach about gel electrophoresis, I have to walk around the room to eight lab groups, demonstrating the micropipettor eight times. If I had this technique on video, then each student could see how to perform the procedure. 5. Anyone who knows science, knows you better have a backup plan. If you are working with living specimen (in my lab, we work with bacteria, termites, betta fish, and crayfish), you know what happens if the organism dies. I think to all the times I've done the termite lab, and the termites just have other ideas besides doing what I want them to do. There are times of year that I've gotten a shipment of termites, and every single one of them is dead. What's the answer? Have the behavior documented on video! I order crayfish for my lab. Wild-caught crayfish. Catching things in the wild - it's a crap shoot. Do you want to take a crap shoot with your lesson for the day? Concurrently, your plan to use videos should have a backup plan. Don't rely SOLELY on those videos, or it will burn you. The wi-fi will go down. Youtube will screw up. You will get a laptop virus. Stuff happens, and you have to have other things to fill the time if your video fails. And NEVER EVER EVER show a video you haven't watched yourself, from beginning to end. I once showed a video to my class on flying squirrels - it was NOT a video about flying squirrels by the end. It's still traumatizing to me, and probably to those kids! 6. Videos can be a good pre-lab. Students often "forget" to read the lab, prior to coming to class. Even if they have enough time, they often don't have the willpower to read many long, scientific paragraphs. This is where videos can come in. "Flipping the classroom" is a technique where the teacher's lecture can be filmed for the students to view at home, and the classroom time is spent actively engaging with the materials. Classroom discussion can happen in a more lively fashion, where the instructor can facilitate and aid, rather than just delivering content to passive students. Many teachers are using Khan Academy videos that are professionally produced, rather than relying on searching for the best cell or DNA video they can find. 7. Videos can provide the diversity that may be missing in your teaching. Like it or not, I'm white and middle class. And I know, that may make some of my students tune out. They might find me annoying, boring, or lame. Much of my department is old, white men. It's just the way it is. Finding new ways to reach out to female or demographically-different students is a bonus that videos can provide. I've seen amazing science videos such as this, by Wu-Tang Clan member GZA, who talks about the scientific method. Whatever it takes to get people excited about science - I'm all for it! 8. Vetting the videos is key. There are a lot of crappy videos on youtube. Videos that make me cringe. Videos that use marketing to lure kids by product placement. Videos that are flat out providing misinformation. Your students will find these videos. Isn't it better for you to find good ones first? I know that my students may not be able to realize that they are being provided with incomplete or inaccurate information. When I teach about cells, I have to watch 10 videos to find that ONE good video to show my class. Students are searching for science topic videos. Vet the videos for them first. In one of my FAVORITE moments of my whole career as a science educator, I was stopped by a young girl in the elevator at my university. She said, "Are you Amy Hollingsworth?" (I got a little scared, I never know where that question is going to go!) I told her yes. She said, "I am in Dr. X's class here MWF, and I just don't understand him at all. I was googling "Biology, University of Akron" and I found your whole set of teaching videos online, and I LOVE THEM! I feel like I know you! And your son is so cute!" I had used lecture-capture for my Natural Science Biology Course, and had filmed my lectures for a whole semester. One day, we had a snow day, and so I had recorded my lecture from home. My four-year-old son had creeped into Mommy's videos, and had actually explained the distribution of fossils in Ohio (I know, I know, but he loves dinosaurs). So I guess that would be point 9. Videos allow the learning to go on, even when teacher or student can't be in class. And I connected to a student who might have not been successful in Biology. And I felt a little like a rock star, with a fan base. If teachers don't use videos to their advantage, they are missing out on a strong pedagogical tool that can supplement learning. This semester, I am filming many of my labs, editing the video, and am going to provide the students with the videos to supplement lab. Point 10. This helps my TAs to get to spend more time helping students do the labs, instead of talking and talking and talking. More activity. Less repetition. Everyone wins! Income Inequality seems to be on the tip of everyone’s tongue lately. President Obama spoke about it in his State of The Union Address on January 28th. He described how the middle and lower classes have stalled in their wage potential, and the possibility of getting by, much less getting ahead, seems to have lessened. Also in the news is the plight of adjuncts – those part-time college instructors who teach one or two classes at a university for a small sum and no benefits. This morning, adjuncts at my university were described in an NPR story, “Part-time Professors Demand Higher Pay; Will Colleges Listen?” The story goes on to describe how “professional adjuncts” – those workers who hold a graduate degree in their field, and who teach as needed at one or several higher education institutions, as their full time job – are essentially making minimum wage, or less. The plight of professional adjuncts is often a sad tale – often we read about how they struggle to make ends meet, selling plasma on the side to supplement their income, Margaret Mary Vojtko who died destitute at the age of 83 as she taught French for 25 years as an adjunct at Duquesne University, to this self-proclaimed “adjunct whore” who describes herself as doing tricks each semester to make ends meet. The horror stories abound. But how did these horror stories come to fruition? I must first divulge my own experiences as an adjunct. I enjoyed my position as a non-major, adjunct biology instructor for 6 semesters at my university. I taught large, stadium-style lectures for classes of 100 to over 300 students each semester. I enjoyed working with these students, even though there were a lot of them, as they worked through the general education requirements of their degree plan. I spent three contact hours a week – either two classes of an hour and a half every Tue/Thur, or three classes of one hour every Mon/Wed/Fri – lecturing, using classroom technology, answering questions, helping the students find videos of concepts they didn’t understand, helping students with campus problems, or just counseling students on problems I could help with, be it personal or academic. Outside of class, I had to order textbooks, sit on review committees, collaborate with other lecture professors, do grades, answer emails (and with 300 students, that’s a TON of email) and make copies. I earned less than $1000 per credit hour for the course. After taxes, for one semester, I would see $399 deposited once a month, five times, into my direct deposit bank account. Take home for one semester of work - $2000. Now here is where I differ from the adjuncts that are often described in the depressing stories you hear about these people with advanced degrees living on welfare and food stamps – I have a full time job. I work at the university already, as a Biology lab Coordinator. 40 hours a week, I work with teaching assistants, supervise 640 lab students a semester, order supplies, write curriculum, do learning management software for the course, and keep a bustling Biology lab exciting and fun. In between writing curriculum and being a single mom who just earned a doctorate, I love to teach a class or two. Most of the classes that are offered to adjuncts are the general education, lower level courses in the 100 or 200 range. I taught the lowest level of Biology course there is offered at this university – the one taught to general education, non-majors students. I know people who adjunct who teach the freshman English classes, the non-major History courses, even Physics! I also have my name and resume in the pool at six other universities/colleges for these types of adjunct positions. I think adjuncting is fun! It allows me to do something I find enjoyable – teaching. But, there’s been no adjunct teaching positions available in my department for the last three semesters, because of grant fluctuations and course load changes for professors. Thank god for my full time job. Adjuncting was NEVER meant to be a full time job. That is the exact reason adjuncts, who are “professional adjuncts,” are in the position they are today. Adjuncting is a part time type of position, meant for people who are professionals in other full time jobs, who essentially “pick up a shift” here or there. They are like substitutes, who are called to fill in when a full time, tenure tract faculty gets a huge grant and the department needs someone to fill in. The people who wish adjuncting was a full time profession are sadly mistaken, and I believe will continue to suffer if they keep trying to push to make adjuncting a full time job with benefits and security. Just as I feel the minimum wage employee at Walmart or McDonalds is futile in fighting for this type of job to support them and their families (these fast food jobs were meant for teenagers who needed part time work, not for someone needing to support a family) – I feel the plight of the adjunct is useless. Someone who has the basic skills to man the fryer, stock the shelves, or teach the most basic of college courses will continue to earn part time employee pay, for low-level, part-time created jobs. Adjuncting is not a career, adjuncting is the burger flipping of higher education. Now please, don’t think I’m dissing on adjuncts. I know how hard, stressful, and overwhelming adjuncting can be as a job. When you have students taking intro courses, they can be the most needy students – the ones who may be taking your course while also taking basic math because they can’t do math, taking basic reading, because they can’t read, or just aren’t cut out for college. You may pour 30 hours a week into one course, to do the justice to your students that you feel, and I felt, they deserve. But the honest truth about adjuncting is that there is no security to it as a profession, it’s low paid work meant for people who have other full time jobs, and it’s something that I would advise ANY person who is getting a graduate degree and plans to go teach “because they love it” to stay away from. Go into secondary education and teach high school students. Find a job at a company that you can do professional development or job training. But if you get your grad degree and plan to “just go teach” instead of having a research agenda that is good enough to get you a tenure track position (and I almost guarantee you are not in that top 5% in your field who will be offered a tenure track job), then you are going to find yourself unhappy, unemployed on a whim of the finances of higher ed institutions, or forced to move somewhere you don’t want to live, working at a university no one has ever heard of. The truth of the matter is that a $80,000 a year job that you don’t have to move for, that allows you to teach a subject you love, with benefits and security, is a fantasy.

And as long as “professional adjuncts” are offering themselves on the altar of higher education in hordes, the market for them is not going to change. Only when ALL adjuncts decide to pursue other job opportunities, that are full time, with benefits, and security, and no one wants those adjunct positions anymore, will higher ed pay more for them. Supply and demand. The brutal truth of education as a business. |

AuthorDr. Amy B Hollingsworth has worked in education for over 20 years. Most recently, she was a Learning Coach at the NIHF STEM School in Akron. She served as the Executive Director of Massillon Digital Academy. She was the District Technology Specialist at Massillon. She also was the Natural Science Biology Lab Coordinator at The University of Akron. She specializes in Biology Curriculum and Instruction, STEM education, and technology integration. She has written six lab manuals, and an interactive biology ebook. She has dedicated her life to teaching and learning, her children - Matthew, Lilly, and Joey, her husband Ryan, and her NewfiePoo Bailey. What's Amy Reading?Archives

December 2014

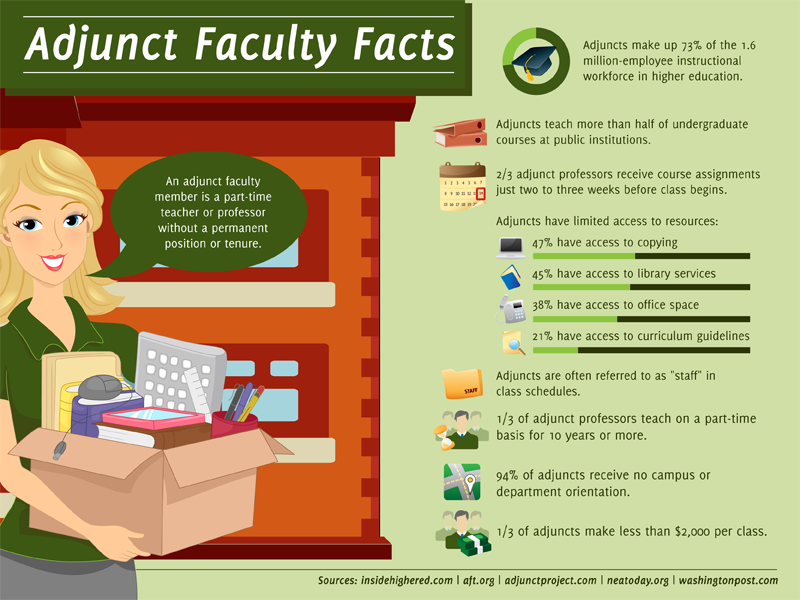

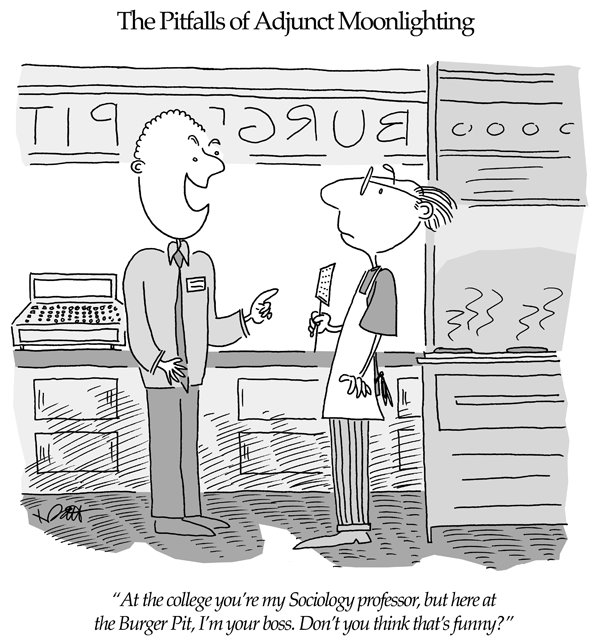

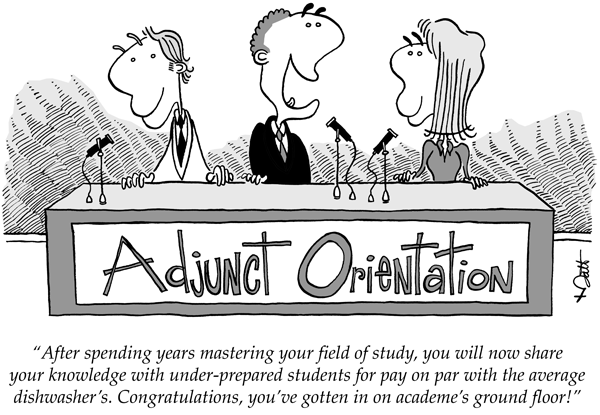

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed