I use Youtube videos extensively in my biology lab for a multitude of different ways to supplement learning. Up until this semester, I have always projected the videos onto the big screen. When I talk about the dangers of DDT, I show videos of soldiers spraying DDT onto prisoners from Japanese internment camps to kill lice, of bald eagles sitting on their nests full of broken eggs, and how the pesticide bioaccumulates in living tissue. Just telling students about these topics is one thing - but showing them historical evidence, the way it happened in nature, and the way the chemicals interact brings the science to life.

1. Making microscopic interaction visible:

“Back in the day when I learned chemistry, there was no YouTube, no videos, and you just had to imagine molecules moving and hitting each other,” Chemistry teacher Jasen Gohn said. “But now you can just bring up a video of, like, salt dissolving.” For my Biology students, reactions like diffusion or osmosis can be made large enough to see. I can also equate the processes to real bodily functions, like kidney dialysis, which brings the human elements to what might have been considered "boring" in the past. Showing my students pictures of DNA and Watson and Crick are one thing - showing them the actual structure of DNA and the way it functions to make life possible is much better. In Biology, much of what happens at the cellular, molecular, and chemical level is not visible to the naked eye. Videos make these interactions viewable.

2. Watching a lecture for one hour is often boring

Many college classes last between 50 and 90 minutes. One study noted that students can pay attention for between 10 and 15 minutes before they look away, stop taking notes, or look at their electronic device. Towards the end of class, note taking ceased, and students could only pay attention for 3 - 4 minutes. Youtube videos can be an engaging, good "distraction" from the traditional lecture. Videos can break up the monotony.

3. More demonstrations can happen in the classroom

Demonstrations are often used for convenience, when the entire class doing an activity would be prohibited by cost or time. When using video demonstrations, students can watch the teacher, instructor, scientist, or star doing the demo on video. Not only is this more economical, it's often more fun. If a student was not paying attention during class (as often happens in this new age of students who work full time, are parents, or who may be distracted) they still have the opportunity to to view the video later.

4. Whether there are 20 or 200 students in the room, each student can have a front row seat.

Anyone who has taught a lab-based science course knows that you often have to go around the room, from lab bench to lab bench, repeating the technique so the students can be close enough to see. In a large lecture, an Elmo-device (basically a stereoscope that projects the demo to a big screen) might make the demo big enough, but it is often difficult to see. When I teach about gel electrophoresis, I have to walk around the room to eight lab groups, demonstrating the micropipettor eight times. If I had this technique on video, then each student could see how to perform the procedure.

5. Anyone who knows science, knows you better have a backup plan.

If you are working with living specimen (in my lab, we work with bacteria, termites, betta fish, and crayfish), you know what happens if the organism dies. I think to all the times I've done the termite lab, and the termites just have other ideas besides doing what I want them to do. There are times of year that I've gotten a shipment of termites, and every single one of them is dead. What's the answer? Have the behavior documented on video! I order crayfish for my lab. Wild-caught crayfish. Catching things in the wild - it's a crap shoot. Do you want to take a crap shoot with your lesson for the day?

Concurrently, your plan to use videos should have a backup plan. Don't rely SOLELY on those videos, or it will burn you. The wi-fi will go down. Youtube will screw up. You will get a laptop virus. Stuff happens, and you have to have other things to fill the time if your video fails. And NEVER EVER EVER show a video you haven't watched yourself, from beginning to end. I once showed a video to my class on flying squirrels - it was NOT a video about flying squirrels by the end. It's still traumatizing to me, and probably to those kids!

6. Videos can be a good pre-lab.

Students often "forget" to read the lab, prior to coming to class. Even if they have enough time, they often don't have the willpower to read many long, scientific paragraphs. This is where videos can come in. "Flipping the classroom" is a technique where the teacher's lecture can be filmed for the students to view at home, and the classroom time is spent actively engaging with the materials. Classroom discussion can happen in a more lively fashion, where the instructor can facilitate and aid, rather than just delivering content to passive students. Many teachers are using Khan Academy videos that are professionally produced, rather than relying on searching for the best cell or DNA video they can find.

7. Videos can provide the diversity that may be missing in your teaching.

Like it or not, I'm white and middle class. And I know, that may make some of my students tune out. They might find me annoying, boring, or lame. Much of my department is old, white men. It's just the way it is. Finding new ways to reach out to female or demographically-different students is a bonus that videos can provide. I've seen amazing science videos such as this, by Wu-Tang Clan member GZA, who talks about the scientific method. Whatever it takes to get people excited about science - I'm all for it!

8. Vetting the videos is key.

There are a lot of crappy videos on youtube. Videos that make me cringe. Videos that use marketing to lure kids by product placement. Videos that are flat out providing misinformation. Your students will find these videos. Isn't it better for you to find good ones first? I know that my students may not be able to realize that they are being provided with incomplete or inaccurate information. When I teach about cells, I have to watch 10 videos to find that ONE good video to show my class. Students are searching for science topic videos. Vet the videos for them first.

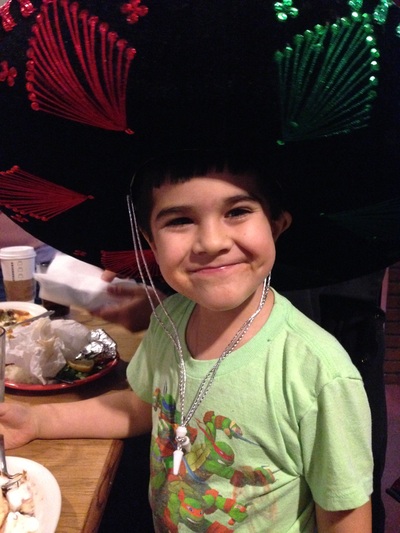

In one of my FAVORITE moments of my whole career as a science educator, I was stopped by a young girl in the elevator at my university. She said, "Are you Amy Hollingsworth?" (I got a little scared, I never know where that question is going to go!) I told her yes. She said, "I am in Dr. X's class here MWF, and I just don't understand him at all. I was googling "Biology, University of Akron" and I found your whole set of teaching videos online, and I LOVE THEM! I feel like I know you! And your son is so cute!"

I had used lecture-capture for my Natural Science Biology Course, and had filmed my lectures for a whole semester. One day, we had a snow day, and so I had recorded my lecture from home. My four-year-old son had creeped into Mommy's videos, and had actually explained the distribution of fossils in Ohio (I know, I know, but he loves dinosaurs). So I guess that would be point 9. Videos allow the learning to go on, even when teacher or student can't be in class. And I connected to a student who might have not been successful in Biology. And I felt a little like a rock star, with a fan base.

If teachers don't use videos to their advantage, they are missing out on a strong pedagogical tool that can supplement learning. This semester, I am filming many of my labs, editing the video, and am going to provide the students with the videos to supplement lab. Point 10. This helps my TAs to get to spend more time helping students do the labs, instead of talking and talking and talking. More activity. Less repetition. Everyone wins!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed